From the road, it looks like progress.

A project site at full stride has a particular kind of confidence to it. Steel ribs climb into the sky. Concrete trucks arrive on schedule. Cranes swing slow, deliberate arcs, placing beams where they belong as if the building is assembling itself. You can stand at the fence line and watch the shape become inevitable.

That’s the kind of progress organizations like to fund: visible motion.

A few weeks later, the renderings start to match the skyline. The schedule looks healthy. The weekly update deck replaces plans with photos. Milestones get checked off, and people start using the word momentum again, as if it were a property of the system rather than a temporary alignment of attention, budget, and goodwill.

But the crew on the ground doesn’t watch the skyline. They watch the footings.

They know which pours were rushed because rain was coming and the date wouldn’t move. They know where the rebar plan got “value engineered” after a budget review. They know which concrete cured under plastic because the weather didn’t cooperate, and which testing cycle was shortened because someone decided it was “low risk.” Nothing looks wrong from thirty yards away. From three feet away, you can see the difference between a foundation that’s done and a foundation that’s merely covered.

The quiet terror of construction isn’t collapse in the cinematic sense. It’s what happens when weight arrives later.

A building can look finished long before it’s safe. A bridge can reach the far bank long before it’s ready for load. The dangerous part is that the cues we’re trained to trust (walls, roofs, spans) are not the same cues that determine whether the structure will hold once people start using it.

Construction has a way to deal with this: load tests. You don’t call a structure “complete” because it looks right. You call it complete because it has been asked to carry weight and didn’t flinch.

Most organizations don’t have an equivalent test for progress.

Instead, progress is declared when motion is visible. When dates hold. When dashboards turn green. Readiness is assumed, inferred, or postponed. The trade is rarely stated out loud, but it’s made constantly: we choose motion because motion is legible, and we defer readiness because readiness is quieter, harder to demonstrate, and inconvenient to headline.

Take a few steps back, and everything reads as success.

Wander closer, and the story changes. The “small” issues aren’t small anymore. The missing tests matter. Temporary shims become permanent. The workaround that kept things moving becomes the thing everyone depends on without fully understanding. Manual steps (reconciliations, reruns, copy-paste bridges) start carrying real load, even though they were never designed to.

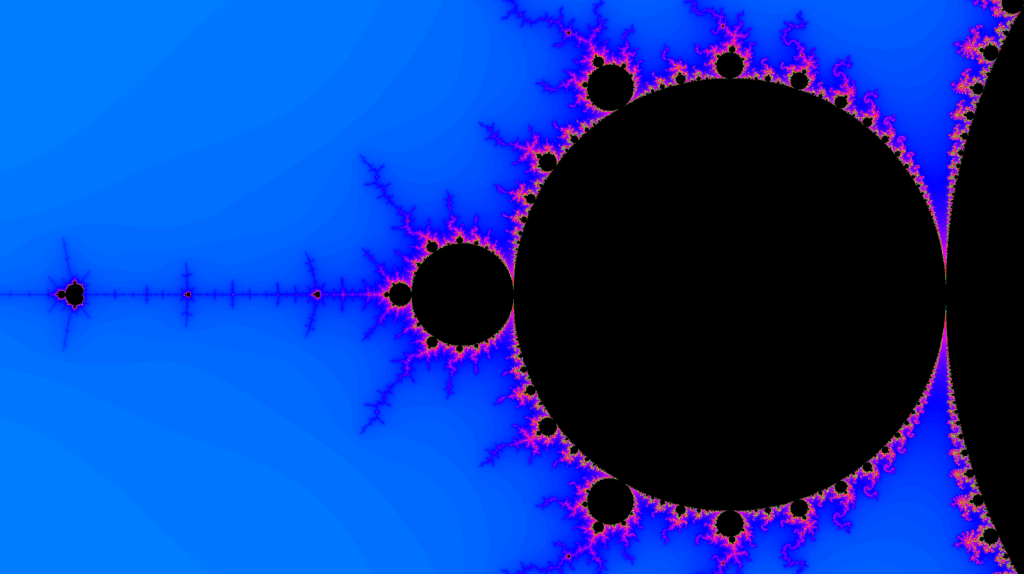

There’s a mathematical term for experiences like this: a pattern that repeats at different scales, where the outline stays familiar even as the details change. A fractal.

The most famous example is the Mandelbrot set: a simple equation that produces an endlessly complex boundary. Zoom in and you don’t find a smooth edge. You find more structure. More loops. More jagged coastline. At every magnification, the shape feels recognizable, but the complexity never resolves.

Organizations behave this way more often than we like to admit.

From high altitude, progress is a clean silhouette: roadmaps, milestones, adoption curves, budget burn, green status lights. Up close, progress is messier: brittle dependencies, manual controls quietly absorbing risk, backlog triage, and the fatigue of people who keep pointing at the foundation while everyone else celebrates the roof.

Risk and dependency behave like a fractal. The language repeats. The meetings rhyme. The updates feel consistent. But distance from ground truth changes what feels real, and what gets funded.

The Org Chart as a Zoom Lens

If the construction metaphor feels uncomfortably familiar, it’s because most organizations already operate on a kind of zoom system. An org chart isn’t only a hierarchy of authority; it also operates as a hierarchy of abstraction.

We talk about “layers of management” as if layers are inherently wasteful, but that’s not really what the middle of the org is doing. In a healthy system, management is an information transport mechanism. It exists because complexity doesn’t survive travel at full resolution.

Every layer, whether formal or informal, has two unavoidable jobs.

First: delegate complexity downward.

Break a broad intent into work that real teams can perform under real constraints. Translate strategy into plans, plans into tasks, and tasks into deadlines.

Second: summarize reality upward.

Convert thousands of moving parts into something a leader can hold long enough to make a decision without dropping everything else they’re accountable for.

That second job is where most organizations quietly get into trouble, because it is inherently compressive.

Summarization isn’t a failure of communication. It’s a necessary distortion. It turns texture into shape and conditional truth into something that can survive a meeting. And like any compression, it has a loss budget: details that will not make the trip.

The problem isn’t that details are lost. The problem is which details.

Time is limited, so messages get shorter. Attention is scarce, so sharp edges are prioritized over slow warnings. Incentives are real, so the tone drifts toward confidence, because uncertainty is often read as incompetence. The higher a message travels, the more “executive readable” it has to become, which usually means it cannot carry too many caveats without becoming unusable.

So the organization adapts. It learns what kind of truth survives altitude.

Instead of, “This will fail under load because the upstream system doesn’t guarantee uniqueness,” the message becomes, “We have some data quality challenges.” Instead of, “We’re staving off a critical dependency with manual reconciliation,” it becomes, “We’ve implemented an interim control.”

Same facts, viewed from different altitudes. What’s missing in that translation is not honesty, but invariants.

An invariant is a condition that must remain true for the system to function, regardless of scope, schedule, or optimism. “IDs are unique end-to-end.” “This process reconciles without human intervention.” “Rollback has been executed successfully outside of an incident.” These are not preferences or risks; they are load-bearing truths.

In most organizations, invariants are rarely named, and almost never enforced across layers. So they are exactly the details most likely to be compressed away.

As information moves upward, the silhouette cleans up. Moving up the org chart resembles zooming out on the fractal: the shape becomes simpler, the boundary looks stable, and progress feels obvious because the rough edges have been averaged out.

Moving downward is the opposite. Zooming in reveals context, exceptions, and tradeoffs. The same words still get used, like progress, risk, alignment, and delivery, but down here they refer to specific failure modes, specific dependencies, and specific compensating behaviors that don’t fit neatly on a slide.

This is how organizations end up holding two truths at the same time without anyone technically lying. At one level, things are progressing. At another, the foundation still isn’t cured.

The gap persists because there is no mechanism that forces unresolved ground truth to interrupt a clean summary. What’s needed isn’t usually more reporting, but tripwires: explicit conditions that, when crossed, prevent a system from being described as healthy.

- “If deduplication exceeds n percent for two consecutive runs, status cannot be green.”

- “If a manual control fires more than n times per period, it is no longer temporary.”

- “If rollback has not been executed, readiness cannot be claimed.”

Tripwires are how organizations preserve fidelity across zoom levels. They ensure that certain facts survive compression, even when they’re inconvenient.

Without them, the system defaults to what always travels best: the clean shape. With them, abstraction remains useful without becoming deceptive.

The 30,000 ft. View

From the top, most organizations look almost elegant.

At executive altitude, the job isn’t to understand every footing and fastener. It’s to keep the structure standing in public while it’s still being built. Leaders optimize for outcomes that are broad, visible, and consequential: timelines that can be defended, commitments that can be met, reputations that can be protected, and narratives that can survive a quarterly call without collapsing under uncertainty.

That isn’t vanity. It’s the physics of scale, and physics still breaks things when ignored.

An executive’s scope is wide by definition. Time is scarce. Attention is fragmented. Decisions must be made across competing priorities with incomplete information, in environments where stakeholders often care less about why something is hard than whether it will be done. So the organization supplies what that environment can consume: dashboards, milestone charts, budget burn, adoption curves, launch dates, and status lights already filtered into something legible and comparable.

At this altitude, progress arrives as motion that can be reported and defended. A project is on track. A partner is engaged. A release is scheduled. Even hard conversations arrive pre-shaped: here are the risks, here are the mitigations, here is the decision we need.

Risk, here, rarely presents as a concrete failure mode. It appears as probability, reputation, and governance. Do we have controls? Can we demonstrate due diligence? Is the risk “managed”? Risk feels like something policy and oversight should contain, rather than something that must be proven under load.

This is where motion and readiness begin to blur.

A roadmap advances. A demo lands. A status shifts from red to yellow. From a distance, the narrative reads as improvement. Meanwhile, the work that actually makes systems survivable doesn’t look like progress at this scale. It looks like delay. It’s hard to headline, hard to celebrate, and easy to trade away when timelines tighten.

So the questions that dominate this altitude are predictable, and reasonable:

- Are we on track?

- Can we accelerate?

- What’s the adoption curve?

- Do we have the right partner?

What those questions cannot see is the difference between a structure that is rising and one that is ready.

At executive altitude, a system can appear stable long before it has been asked to carry weight. Dashboards show movement, not proof. Green status often means nothing has failed yet, not that the system has survived stress. Readiness is inferred from confidence rather than demonstrated through tests.

The trade is rarely named, but it’s made constantly: motion over readiness. Motion is legible and defensible. Readiness is quieter, slower, and harder to summarize. When abstraction smooths reality, motion wins by default.

The result isn’t recklessness; it’s blind spots. From far enough away, a bridge that hasn’t been load-tested and a bridge that has look identical. Both reach the far bank. Only one deserves trust.

Zooming out makes coherence visible. It also hides fragility. Without mechanisms that force proof to travel upward (load tests, invariants, tripwires) executive decision-making will naturally optimize for the signals it can see.

Next, we step down a level, where the same progress is still real… but it starts to arrive with an asterisk.

Progress with an Asterisk

Middle management lives in the compression layer. If executive reality is shaped by what can be seen at a distance, this layer is shaped by what cannot be ignored up close, but also cannot be carried upward at full resolution.

A manager in the middle owns a slice of their leader’s responsibility. They translate strategy into execution, turning broad intent into sequencing, staffing, deadlines, and tradeoffs, and translate execution back into language leadership can act on: what’s on track, what’s slipping, what decisions are needed, and which risks require air cover.

They are responsible for the handoff between two different worlds. That responsibility comes with leverage, whether it’s acknowledged or not.

From this position, reality arrives as partial truth. There is enough detail to see that the system is messy: dense dependencies, brittle integrations, competing priorities, and failure modes that never appear on dashboards. At the same time, there is constant pressure to keep the machine moving. The job is not simply to describe what is wrong. It is to make progress possible while the problems are still unresolved.

This is where “green” quietly becomes a narrative judgment rather than a demonstrated condition.

In most organizations, green does not mean “this has survived load.” It means “someone believes it will.” Construction doesn’t work that way. A beam isn’t on track because it looks straight; it’s on track because it has carried weight without yielding. Until load is applied, certainty is theatrical.

Because organizations rarely define equivalent load tests for progress, the language at this layer develops a tell: the chronic but.

- We’re progressing, but we’re relying on a manual control.

- We can hit the date, but we’re carrying risk into production.

- The demo will work, but the edge cases aren’t resolved.

- The numbers reconcile, but only if the spreadsheet runs every Tuesday at exactly 0800.

None of these statements are false. They are accurate descriptions of reality in its most portable form. As the message travels upward, the asterisk fades.

- A release is green even if rollback has never been exercised.

- A platform is “ready” even if the on-call path exists only in Slack lore.

- A dependency is “low risk” even if reconciliation is manual, undocumented, and performed by the same two people every month.

The asterisk exists because readiness was assumed, not proven.

This drift is not driven by bad intent. Middle managers learn quickly what kind of reality survives escalation. Leaders cannot ingest raw complexity at scale, and a status update that tries to carry every dependency and caveat becomes unreadable. Unreadable often gets treated as unhelpful.

Incentives reinforce the lesson. The person who consistently brings unresolved risk becomes “the blocker,” even when they’re simply describing physics. In a pressured organization, anything that slows a timeline competes with everything else that is already late. So people adapt. They learn which phrasing gets resourced and which gets politely acknowledged and then ignored.

This is where social survival begins to shape reporting, and where neutrality quietly becomes a choice.

The manager who controls status language, gating criteria, or release definitions is not only describing reality; they are shaping what reality is allowed to be called complete. Compression is unavoidable. Silence is not.

Over time, caveats become background noise. Risks get translated into “manageable issues.” Firefighting stops being evidence of systemic brittleness and starts being framed as resilience. Manual work becomes invisible scaffolding: hours spent reconciling data, rerunning jobs, patching integrations, and bridging gaps by hand. None of this appears on roadmaps. It lives off the books, absorbed into evenings and institutional memory.

Progress continues, but it is being subsidized by attention and fatigue.

Eventually, the asterisk stops being mentioned at all. The workaround becomes the process. The temporary control becomes permanent. The story that travels upward gets cleaner, because the mess has been absorbed locally.

This is the defining feature of the middle zoom. Progress is real. The asterisk is real. And the job of this layer is to keep both true at the same time, at least long enough for the next steering meeting, the next milestone, the next deck.

Unless something interrupts the translation, this is where truth thins out.

What breaks the pattern isn’t more narrative detail, but structure: escalation that survives compression. A single artifact that forces specificity: failure mode, blast radius, trigger condition, mitigation, and the decision required by a date. Not to dramatize risk, but to prevent it from dissolving into reassurance.

Without that structure, the middle layer does exactly what it is optimized to do: keep the machine moving.

And then we step down again, to the level where the asterisk isn’t a footnote. It’s the entire operating manual.

The Ground Truth

At the bottom of the zoom stack, the organization stops being a silhouette and becomes a set of contact points. This is the level where dependencies have names, timestamps, and owners.

Not “integration risk” in the abstract, but the upstream system that sometimes duplicates keys. Not “data quality challenges,” but the field whose meaning changes by region, the mapping table that hasn’t been updated since Thursday, the extract that fails quietly on weekend runs and leaves no alert behind. Not “process,” but the exact sequence of steps that keeps the numbers tied out: the manual reconciliation, the file that has to be moved by hand, the checkbox that must be clicked in the right order because nobody trusts what happens if it isn’t.

Individual contributors see the system as it actually exists: an accumulation of brittle points held together by compensating behavior.

They see the backlog that never becomes important until it explodes. The tickets closed as “won’t fix” because there’s no appetite for foundation work when the schedule says glazing. The decisions that get deferred because the cost of being wrong is immediate, while the benefit of being right is abstract and deferred.

They also see something more subtle: where invariants are already broken.

Uniqueness that only holds most of the time. Automation that works until volume spikes. “Temporary” controls that fire often enough to be load-bearing. These violations are obvious at this level because they show up as work: extra steps, extra checks, and extra vigilance. This is where the manual work tax is paid in hours, attention, and fatigue.

Early on, escalation still works.

When problems are new, the warning signals are high quality. People document risks, propose mitigations, and describe failure modes precisely. They write careful notes, build small proofs, and point at the footing and say, plainly, “This won’t carry load the way we think it will.”

Then comes the middle phase: repetition.

The same risks are raised again. The same dependency appears in a different meeting. The same workaround shows up in a new workflow. The warnings get rephrased, softened, routed through new channels, and attached to new milestones. And still, nothing structural changes, because the next deliverable is due, the budget is already committed, or stopping now would make the timeline read as failure.

Eventually, the late phase arrives: silence.

This is rarely because the problems disappeared, but because the people closest to them stopped believing that describing reality changes outcomes. Status updates shrink. Reporting becomes tactical. “Just get it done” replaces diagnosis. Burnout doesn’t always look like quitting; sometimes it looks like continuing to do the work while not repeating the truth.

This is the moment where organizations don’t stop failing. They stop hearing about failure early enough to prevent it.

Down here, process turns into ritual. Stability turns into superstition. Maintenance becomes triage. Competence becomes invisible scaffolding, all of the unrecorded labor that keeps the floor from sagging while everyone else keeps celebrating the roof.

By the time silence sets in, the organization is already dependent on people remembering which steps matter, which alerts can be ignored, and which assumptions are unsafe but unavoidable. This is what it looks like when escalation has no tripwires and no proof thresholds. When reporting risk does not change status, and status does not change decisions.

When escalation stops changing outcomes, escalation stops.

What This Becomes

If you step back from the personalities involved, the pattern starts to look less like neglect and more like geometry.

Most organizations don’t drift into dependency because leaders are cruel, managers are duplicitous, or individual contributors are unwilling to communicate. They drift because abstraction creates distance, distance reshapes urgency, and urgency determines what gets funded.

Indifference isn’t always a moral failure. More often, it’s epistemic distance: the simple fact that you cannot feel a blast radius you never stand inside.

When you’re close to the system, each risk has mass. You can point to the dependency and name the failure mode. You can see which manual steps are holding the line, which controls have become load-bearing, and which “temporary” fixes are only temporary because no one has yet admitted they’re permanent.

From farther away, risk changes shape. It becomes probabilistic, reputational, and procedural. It turns into categories like “managed,” “acceptable,” or “within tolerance.” It lives in policy language, steering committee notes, and governance decks. This isn’t deception; it’s the only form risk can take at altitude.

Leaders cannot personally verify every footing. They rely on signals: dashboards, summaries, trendlines, and confidence. That reliance is reasonable, even when the consequences of getting it wrong are not.

- If you don’t see the foundation, you keep paying for roofs.

- If you don’t feel the blast radius, you don’t fund blast shielding.

- And if the only version of reality that reaches you is the version that fits on a slide, you will naturally optimize for the things slides can show: motion, adoption, milestones, forward progress.

This is why the outcome feels inevitable. Every layer believes it is behaving rationally.

Individual contributors surface ground truth and propose mitigations. Middle managers compress that ground truth into something leadership can act on. Executives make decisions using the only information that survives the journey upward. No single layer is “the problem.” The problem is the loss of fidelity as reality travels.

You can think of it as a compression gradient. Raw reality at the bottom becomes formatted reality in the middle and narrative reality at the top. Each transformation makes the message easier to carry, easier to align around, and easier to defend. It also strips away the details that would force the organization to slow down, revisit assumptions, or fund unglamorous work.

Over time, that gradient reshapes behavior.

Caveats fade into background noise. Manual work becomes invisible. Temporary workarounds become normal operating conditions. Escalations get rephrased until they no longer interrupt momentum. Eventually, the people closest to the system stop believing that precision changes outcomes, so they stop sending it with full force.

This is how benign indifference forms.

Rarely as a conscious decision to ignore the foundation. Almost always as the natural result of a structure that rewards clean shapes over messy truths. By the time the organization realizes it has become dependent, the dependency isn’t a surprise. It’s simply the architecture it has been quietly building, one reasonable summary at a time.

Translators, Owners, and Architects

If abstraction is the force that smooths reality into a clean silhouette, then the antidote isn’t more reporting. It’s a missing organ: people who can operate at multiple zoom levels without losing fidelity.

Every organization has specialists. What many lack are translators. Not translators in the sense of “turn technical into simple,” but in the more demanding sense: people who can take ground truth and convert it into executive-legible risk without compressing it into meaninglessness. People who can preserve what matters as information travels upward.

This role isn’t defined by title. It appears wherever someone is accountable for making systems survivable over time.

Sometimes it’s an architect who speaks in load-bearing terms: what must be true for the design to hold, what fails when an assumption breaks, and what will become brittle if the organization keeps building upward without rework. Sometimes it’s a system owner who can say, plainly, “If we ship this as-is, we are committing to a manual control indefinitely.” Other times it’s a senior SME or principal engineer who can take a vague risk statement and pin it to a specific failure mode. Sometimes it’s a data steward or platform owner who treats definitions as infrastructure rather than documentation. Sometimes it’s a program lead with enough technical literacy to distinguish “we’re on track” from “we’re shipping risk.”

What these people actually provide is continuity of truth. They prevent the organization from losing its map as reality moves across abstraction layers. They establish defensible constraints; boundaries that are not vibes, aspirations, or policy language, but statements grounded in how the system actually behaves.

They name invariants: the conditions that must remain true for progress to be real rather than cosmetic. They also define how those invariants are tested.

One way to think about this role is simple: they define the load tests for progress. Not metrics that show motion, but conditions that must be satisfied before motion is allowed to count as success.

- A system is not “ready” until rollback has been executed end-to-end outside of an incident.

- A dependency is not “stable” while reconciliation requires recurring human intervention.

- A data contract is not “established” until violations are observable, alerting, and owned.

- A manual control that fires more than n times per period is no longer temporary; it has failed its load test.

Rather than flooding leadership with caveats, these roles create clear thresholds and tripwires. If this metric moves, if this dependency drifts, if this control becomes manual more than n times, we have crossed from inconvenience into structural risk. They turn “we have some challenges” into “here is the failure mode, here is the blast radius, and here is the decision required by this date.”

They also insist on exit paths: Portability plans. Rollback strategies. Substitution options. Observability that makes drift visible before it becomes a public incident. In construction terms, they insist on load testing before inviting people onto the bridge.

These practices don’t slow delivery. They redefine what delivery means. They turn optimism into a hypothesis that must survive contact with reality. There is an uncomfortable truth embedded here: these roles redistribute power.

When someone can name invariants and demonstrate failure modes, vagueness stops being a shelter. When ground truth can be translated into specific, defensible risk, optimism stops functioning as a substitute for readiness. When an organization has people who can speak credibly across layers, it becomes harder to fund skylights while quietly assuming the foundation will somehow hold.

That friction can feel inconvenient in the short term. In the long term, it is often the difference between an organization that owns its systems and one that merely operates them until the scaffolding gives out.

The Risk

Taken together, the failure modes described so far don’t stack linearly. They compound.

Visible motion is rewarded. Disciplined use is not. Adoption incentives favor rollout over readiness, while public narratives reward speed and novelty over survivability. Review processes proliferate, audits accumulate, and trust erodes through drift and theater; controls that slow systems without making them safer.

Meanwhile, understanding gets leased instead of integrated. Knowledge migrates into vendors, tools, and tacit workarounds, while accountability remains internal. Over time, the organization becomes a tenant in systems it is still responsible for, without retaining the leverage that ownership requires.

Fractal abstraction is what allows this to persist. At every layer, the story sounds reasonable. Progress is reported. Risks are “managed.” Dependencies are described as temporary. No single group sees the full cost of what is being absorbed below, because that cost is distributed across time, teams, and people who have learned to keep the machine running quietly.

The result is normalization, not chaos.

Brittle systems that look modern from the outside. Manual scaffolding that was never removed because it’s carrying too much load. Rework, reruns, and rollbacks that quietly consume capacity without ever appearing on roadmaps. Burnout that gets diagnosed as a staffing problem instead of a structural one. A culture that slowly equates confidence with leadership, because confidence travels better than truth.

As invariants erode, exit paths disappear. Manual controls become permanent. Temporary dependencies become assumptions. The cost of change rises, but the visibility of that cost does not. By the time the organization recognizes the dependency, it is no longer a choice. It is embedded. The fractal has repeated itself enough times that the shape feels natural.

That’s the real risk. Not any single decision being wrong, but the accumulation of reasonable decisions, made at the wrong altitude, that quietly construct an organization unable to see what it depends on until it fails.

Mitigation Options

If the problem were simply bad tools or inattentive leaders, the fix would be obvious. But when the failure mode is abstraction itself, mitigation has to be structural.

This isn’t about best practices or presentable maturity models, but rather about designing organizations so truth can survive travel. Most organizations do not (and should not) immediately try to implement all of these – the change described below is much closer to a cultural overhaul than a policy document, and should be approached over time.

Structural practices (difficult, but real)

1. Fund foundations as first-class work

Definition work, data contracts, platform ownership, refactoring budgets, and operational hardening are not cleanup tasks to be deferred until after delivery. They are load-bearing work.

If they aren’t funded explicitly, they will still be paid for later; through rework, outages, and individual heroics that never appear on a balance sheet. The difference is that explicit funding buys choice; deferred funding buys inevitability.

A simple test applies: if removing this work would cause progress to collapse under load, it is not optional.

2. Define load tests for progress, not just milestones

“Green” cannot be a matter of confidence. It must be a demonstrated condition.

Every major initiative should have explicit readiness tests that block status claims until they are satisfied. Not metrics that show motion, but conditions that prove survivability:

- Rollback has been executed end-to-end outside of an incident

- On-call ownership is documented, exercised, and staffed

- Critical reconciliations are automated or explicitly accepted as risk

- Data contracts are published, observable, and enforced

These tests may slow delivery. They also redefine what delivery means, and in doing so, turn optimism into a hypothesis that must survive contact with reality.

3. Put a price on invisibility

Manual steps, shadow processes, reconciliations, reruns, and repeated rework are never free. They are an operational tax paid in human attention.

Track them deliberately: hours per week, frequency of intervention, number of handoffs, number of “temporary” controls still firing. This is not to shame teams, but to make hidden load visible at the same altitude as roadmap progress.

What isn’t counted cannot compete for funding. What remains invisible becomes structural.

4. Name invariants and install tripwires

Some truths must survive compression.

Identify the invariants, the conditions that must remain true for progress to be real rather than cosmetic, and make them explicit. Then define tripwires that interrupt clean status when those invariants are violated.

- “If deduplication exceeds n percent for two consecutive runs, status cannot be green.”

- “If a manual control fires more than n times per period, it is no longer temporary.”

- “If rollback has not been executed, readiness cannot be claimed.”

Tripwires are not punishments for the responsible team. They are the tool that allows organizations to prevent risk from dissolving into reassurance.

5. Make escalation structural, not personal

Escalation should not depend on courage, persistence, or social capital.

Create a standard artifact that survives upward travel: a single page that captures the failure mode, blast radius, trigger condition, mitigation options, and the decision required by a specific date. Not to dramatize risk, but to prevent it from being endlessly reframed.

If raising risk does not change status, scope, or resourcing, the system has taught itself to prefer silence.

6. Require exit paths and observability as entry criteria

If a system cannot be audited, rolled back, substituted, or monitored for drift, it is not infrastructure. It is a bet.

Portability plans, rollback strategies, substitution options, and behavioral observability should be procurement gates rather than afterthoughts. These are the mechanisms that prevent organizations from becoming tenants in systems they remain accountable for.

Cultural practices (necessary, but not sufficient)

Structure alone is not enough. Organizations must also normalize boring progress: the work that may not demo well but reliably reduces future risk. Accurate status updates must be rewarded more than comforting ones. Shared language for readiness, risk, and dependency must be built deliberately, so “on track” means the same thing at every zoom level.

Culture cannot compensate for missing structure. But without cultural reinforcement, even good structure erodes.

The guardrail leaders need to keep close

If you can’t explain what changed and why it works, you bought output instead of capability.

That sentence is not a slogan. It’s a test. Organizations that apply it consistently don’t move slower overall. They simply stop mistaking motion for readiness, and roofs for foundations.

The Mandelbrot Lesson Applied

From the road, the project still looks finished.

That’s the seduction of distance. At the right angle, with the right lighting, steel and drywall read as certainty. The schedule reads as control. The dashboard reads as health.

And in fairness, some of it is progress. Roofs matter. Spans matter. Visible motion is not imaginary. The mistake is treating that silhouette as proof that the load-bearing work is done.

The fractal isn’t the enemy here. It’s simply a property of scale. Large systems can’t be seen all at once, and they can’t be communicated without compression; as a result, abstraction is unavoidable, as are layers. So is the fact that “on track” can be true at one zoom level while the foundation remains untested at another.

What changes the outcome isn’t wishing the fractal away. It’s designing organizations so truth survives crossing it.

That means building routes where ground truth can travel without being smoothed into reassurance. It means funding work that may never headline well but carries real load. It means insisting that readiness is demonstrated rather than narrated. And it means remembering that the people closest to the system are rarely being pessimistic; they are usually being precise.

The Mandelbrot set teaches a simple lesson: you can keep zooming and still find structure you didn’t account for. The boundary stays familiar, but the details keep arriving.

So if you want fewer collapses, don’t demand that reality become simpler. Build organizations that can hold reality at multiple resolutions, without losing what matters as you zoom out.

Progress seen at altitude is still progress. But it isn’t proof.

Leave a comment