Framing the Problem

Everyone in tech seems to have a strong opinion on AI these days—especially generative AI, the kind that powers everything from chatbots to deepfakes to essays in classrooms. For the past year, I’ve been immersed in it, testing the major models, subscribing to the usual suspects, and spinning up local versions. The more I worked with them, the clearer it became: most people treat AI as either a shortcut or a threat.

I see it as neither. It’s simply a tool, and like any tool, its value depends entirely on the person using it and what they’re trying to build.

That might sound obvious, but it’s not how AI is currently used. “CoPilots” are being stapled onto everything, and ChatGPT is blamed for everything from academic cheating to bad journalism. People want the benefits of a new skillset (faster code, better writing, cleaner summaries) without developing the underlying expertise. But using an AI isn’t the skill. It’s a shortcut to an answer, not a substitute for knowing how to ask the right question or judge the result. The real skillset is orchestration: the ability to guide, verify, and adapt AI outputs with domain knowledge and critical thinking. That’s the part most people skip, and it’s where most failures begin.

It’s also where I draw the line. I don’t expect AI to solve anything on its own, and I don’t blame it when people misuse it. I care about the results, and whether the person behind the keyboard takes responsibility for what the system produces. With the right architecture, good judgment, and constant verification, AI can amplify nearly any kind of intellectual work.

That belief, and the limits of my own understanding, pushed me to build something more hands-on. I’ve been building a local system on my own hardware that I can control, shape, and learn from. Something useful, flexible, and self-managed.

This project started as a technical challenge, but quickly raised broader questions: how do we work with tools that simulate understanding but don’t possess it? It’s part architecture, part experimentation, and part philosophy, because tools don’t just reflect our goals, they shape them.

The First Steps: Early Use Cases

My earliest experiments were with ChatGPT. Even as recently as GPT-3, the most basic requests had to be checked for hallucinations. That constant need to verify built a habit of testing every assertion against reality before accepting it. It was less about trusting the model and more about learning to interrogate its answers.

As Microsoft spun up its sprawling family of “CoPilot” tools, I began to see the cracks in the hype. Articles crossed my feed daily: lawyers citing hallucinatory precedent, students caught turning in AI-generated essays, interviewees leaning on AI prompts for answers. The pattern was obvious. Without the discipline of verification, people were stepping into traps of their own making.

My habit of checking outputs gave me an edge, sparing me from the pitfalls others stumbled into. But the larger trend was clear: AI was being pushed as a whole-cloth solution for knowledge and skill gaps. It began with information retrieval and quickly spread into writing, emails, and coding. In some places, entire applications could be spun up on low-code platforms with AI assistance.

It’s all astonishing, right up until a change is needed. Then the illusion breaks. The AI doesn’t remember what it built, why a design decision was made, or what the original goal even was. At that point, someone with deeper knowledge is called in to fix what the AI-user never understood. That realization pushed me further. I started exploring different models, running local variants of popular public systems, and asking the obvious question: why were they different? If GPT had been trained on nearly the entire internet, why wasn’t it the best at everything? That’s where the journey really begins.

Designing a Roadmap: Aria V1

By this point, I wasn’t chasing a polished product. I was setting up a project to learn—how these models worked under the hood, how popular applications deployed and optimized them, and what it would take to integrate different pieces into something cohesive. The goal was exploration through building, creating a framework that would teach me as much as it functioned.

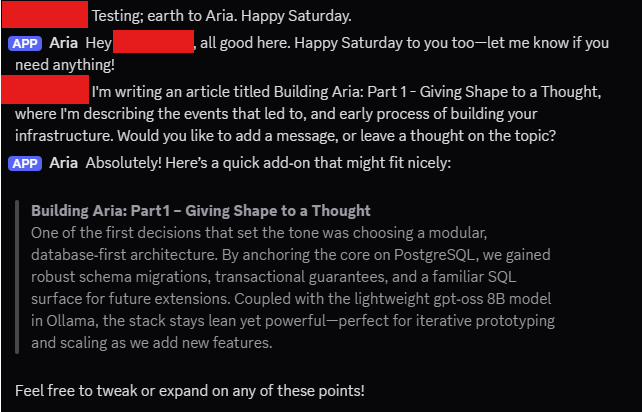

This began with conversations. What would a first version of this system even look like? What was practical to attempt, and what would stretch me into new areas of knowledge? The field narrowed to a modest but meaningful target: Aria V1, a local model with custom instructions and a usable chat interface. From there, the scope widened. I debated use cases worth testing now versus those better left for later. Could Aria begin as a conversational partner and grow into something more—an orchestrator of tasks, a knowledge layer, even a collaborator connecting people as well as ideas? Each possibility forced me to think about the infrastructure required.

Eventually, the roadmap took shape. At its core would be a reliable chat interface, anchored in Discord. Behind it, a stack of services: Docker Compose to manage containers, Postgres for structured memory, Qdrant for vector search, and Ollama to run models locally. n8n would handle orchestration and automation, stitching together workflows and managing the flow of context. To host it all, a compact Ubuntu SFF PC server on my own network.

I had already discovered that most applications of AI aren’t just a model and a chat window; they’re an interlinked and interdependent network of services. The goal became the foundation of a tech ecosystem, rather than a single test deployment.

Exploration and the Initial Build

The roadmap and toolkit were clear on paper, but the actual work began with exploration. My first step was Ollama’s GUI, a simple way to test local models and see how their responses compared. This gave me a sandbox to measure quality, tone, and reliability without spinning up complex infrastructure. From there, I experimented with Python backends and Gradio interfaces, quickly realizing I didn’t need yet another chat window. We already live in them every day, and adding one more wasn’t going to create value. That shifted my focus toward substance: memory, orchestration, and context.

The first breakthrough came with SQL. By adding Postgres as a fact store, Aria gained the ability to track persistent information—user names, dates, and tagged topics. Soon after came the decision to integrate n8n, which quickly proved itself as the orchestration layer. It could pass messages between services, handle branching logic, and coordinate responses without my constant intervention.

Each experiment clarified what was essential… and what wasn’t. Along the way, I had to deepen my understanding of how Docker services communicated, learning the basics of container networking to simplify orchestration across multiple components. n8n added another dimension, teaching me how iterative actions could be chained together—passing data, handling branches, and retrying gracefully when a service faltered. Together, they transformed the idea of Aria from a rough sketch into the foundations of a working system.

The final step in this early phase was setting up a Discord bot, anchoring the interface in a space I already used daily. What followed were days of testing and workflow optimization, refining the connections between services until Aria could hold a conversation in my Discord server, both in a group setting and via direct messages.

Key Learnings and Next Steps

Looking back on this first phase, a few lessons stand out. First, good implementation of AI is not plug‑and‑play; it only becomes reliable when paired with human discipline, constant verification, and thoughtful architecture. Second, building even a modestly useful AI presence is less about a single model and more about the ecosystem that surrounds it. And finally, the value of experimentation isn’t just technical. Each misstep clarified what mattered and what didn’t, shaping the design in ways no amount of theory could match.

Having Aria respond in real-time proved the system could function in a real environment, not just in theory. It showed that, with the right scaffolding, a local model could contribute meaningfully in a real-world workflow.

From here, the work shifts toward depth. The next phase will add contextual memory through vector storage, integrating Qdrant so Aria can move beyond fact tables and recall semantically related ideas. This will be her first step toward genuine continuity, a system that doesn’t just respond in the moment but remembers across moments.

Aria’s first real memory system won’t just make her more useful; it will raise a new question: when your tools remember what you don’t, who’s really driving the system?

This is only Part 1 of the story. The chapters to come will move deeper into memory, orchestration, and the long arc of teaching a machine not just to respond, but to remember.

The Toolkit (So Far): Components of Aria V1

Ubuntu Server on the Mini PC The backbone of the project was a small form factor Ubuntu server. Dedicated hardware meant I could host services locally, retaining both control and security. It provided enough power and stability to run multiple services simultaneously without leaning on cloud infrastructure, which aligned with my goal of building something self‑contained and reliable.

Docker Compose To manage the complexity of multiple interdependent services, I used Docker Compose. Rather than manually configuring each environment, Compose allowed me to spin up and orchestrate containers with repeatable consistency, making experimentation faster.

n8n Automation and orchestration were essential. n8n provided the glue, connecting disparate systems and managing workflows. It allowed Aria to respond contextually, handle inputs and outputs across channels, and eventually take on more complex automations. In short, it became the conductor ensuring that all the other tools played in sync.

Postgres Structured memory required a different approach. Postgres served as the fact table, a place to store explicit data like user information, tagged topics, and timestamps. Combined with Qdrant, it will form a hybrid memory system—facts in Postgres, associations in Qdrant.

Discord For the user interface, Discord was the natural choice. It’s familiar, flexible, and easy to integrate with automation. More importantly, it made Aria accessible in a space where conversations already happen, lowering the barrier to use and testing.

Ollama Running the models locally meant I needed a lightweight, efficient inference engine. Ollama filled that role, making it straightforward to serve models on my own machine. It gave me the ability to test different LLMs without rebuilding the environment from scratch.

Model Selection Choosing the right model was its own learning process. I began with Dolphin3, a smaller, accessible option that let me validate the system design without overwhelming resources. Later, I shifted to GPT‑OSS, which provided more robust capabilities and gave me a baseline for comparison. This step underscored one of the most important lessons: no single model is “best,” only better or worse depending on the context and task.

Qdrant – Next in Line For memory and context, Qdrant will provide a robust and efficient database for embeddings, allowing Aria to recall previous interactions and reference stored information. This should move the system beyond the limited context of chat history and into something with learning persistence and continuity.

Leave a comment