Picking Up the Thread

In Part 1, Aria reached her first milestone: she was live in a practical sense. Running locally in Docker, serving models through Ollama, and speaking through Discord, she could already respond in conversation. Messages flowed into Postgres, the last ten entries recalled with each new exchange, giving her a baseline of context. She could even check whether she was being spoken to by scanning for her own name before replying. This was more than a technical proof of concept, it was a ‘voice’ that could carry a conversation, be tested, and gradually be refined.

My purpose in building Aria was never just to wire together the latest stack insert or clip on the next shiny function. I actively chose not to pursue the addition of MCP layers this week, though they are still on the list. For readers less familiar with the acronym, MCP refers to the “Model Context Protocol,” a newer standard for coordinating model inputs and outputs.

It’s a promising addition, but skipping it here illustrates the broader point: the goal is not to collect features, but to understand what each piece actually does and whether it is necessary. By the time Docker updated with the MCP library, I had already engineered a custom node with a tool call prompt and lightweight conversion scripts to transform her string responses into JSON, covering the same ground without extra complexity.

Through this project, I want to understand what is happening beneath the surface of the chat interface and branding. Too often, AI is treated as a black box; applied like a plugin, expected to deliver results without question. In my experience, that approach builds neither trust nor resilience. So, I’m interested in learning how the technology actually works: where context lives, how memory is simulated, how components interact, and what trade-offs sit beneath the convenience of “it just works.”

In essence, each evolution of Aria is a way to peel back the abstraction and see the mechanics at work; to gain fluency rather than dependency.

Teaching Aria Tools

The next step was giving Aria the ability to act through tools. Until this point, her responses came only from the text prompt and surrounding conversation history. She could carry a discussion, but she had no way to reach into other systems—no memory to query, no knowledge base to search, no mechanism to store information for later. I knew from the start that the real value would come once she could extend beyond base training and her system prompt.

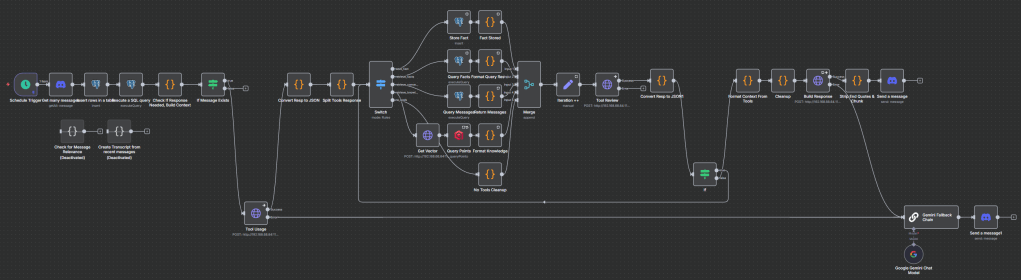

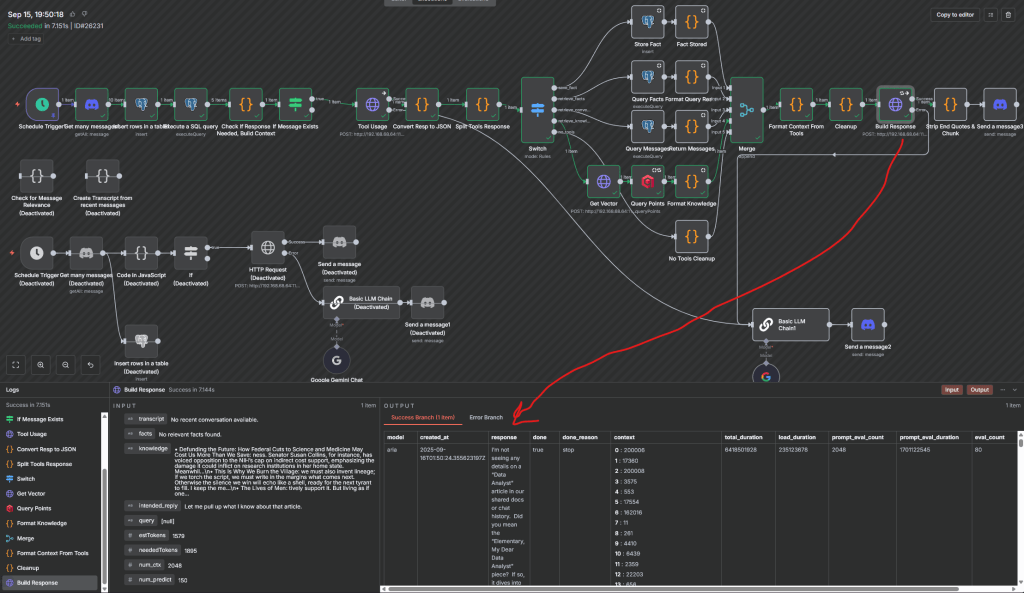

The tool usage node was how I opened that door. Think of it as a switchboard operator. On one side, a message comes in from a Discord DM or chat channel. On the other side sit a handful of defined options: fact storage, fact retrieval, vector search through my article corpus, or simple direct reply. Instead of improvising everything in free text, Aria now receives a clearly labeled set of choices and instructions for when each is appropriate. The node itself isn’t complicated, it’s just a second prompt with stricter rules, but the impact is dramatic.

I deliberately tuned the environment around this node as we implemented the tools themselves and tested. The context window was shortened to keep the focus narrow. The temperature (a parameter which controls randomness in model outputs) was lowered so her choices stayed consistent rather than wandering into creative but irrelevant paths. And the available tools were spelled out in plain language: what they do, when to use them, and what the output should look like. Alongside those instructions, I passed the most recent message plus the last ten from the channel, so her decision could be grounded in the actual flow of conversation.

Each part plays a role. The shorter context reduces noise. The lower temperature makes her behavior more repeatable. The explicit tool descriptions remove ambiguity, so a request that once would have stopped at her text generation now translates into a structured choice like “retrieve_facts” or “search_knowledge.” And by requiring her output to follow a JSON‑like structure, I created a predictable contract: other nodes in n8n could parse the response, act on it, and return results reliably.

This wasn’t an afterthought bolted on later; it was planned as a way to expand her from the beginning. Of course, there was plenty of testing and tuning after the structure was laid: refining how instructions were worded, tightening context, and adjusting formats until the system behaved predictably. But the principle held steady: if Aria was to act, she needed a controlled way to decide which tool to use and when.

Seen in practice, this structure turned a simple question like “Aria, what’s the last thing I told you about deliveries?” into something more than a guess. She could select the fact retrieval tool, query Postgres, and deliver the actual stored information. Likewise, a request to reference an article or a concept I’ve written about would push her toward vector search in Qdrant. If neither applied, she would default to a conversational reply.

What this really unlocked was confidence. I no longer had to infer whether she might choose correctly, or hope the tools would run. I could see, in structured outputs, which tool she picked and why. When she succeeded, the system worked as designed. When she didn’t, I could refine the rules or adjust the instructions. That feedback loop made the architecture sturdier, shifting her role from a reactive generator of text into an orchestrator of functions.

This structure matters. By constraining her options and providing explicit decision rules, I gave her the beginnings of agency. She could evaluate, choose, and act within defined parameters. That clarity not only made her responses more reliable, it also set the stage for deeper forms of capability; where using the right tool at the right time becomes as important as generating the right words.

How Aria Learned to Pretend She Remembers Me

Once Aria could act, the next step was giving her something worth acting on. Context alone wasn’t enough. If every answer had to be built from scratch each time, she would never accumulate continuity. Memory, in both structured and associative forms, was the natural next layer.

This, I approached in two pieces. First came the relational side: two Postgres tables, one for messages and one for facts. The messages table serves as a running log of conversations, storing channel, sender, and timestamps alongside prompts and responses. This gave us not only history to query, but also a record of performance: what Aria saw, what she answered, and how the interaction evolved. The fact table, by contrast, was more deliberate. Aria could decide to store something explicitly; like “Jeff = Dominije = Dom”, and later retrieve it by user or by date range. That distinction matters. The log gives breadth of context, but facts give a more immediately useful depth.

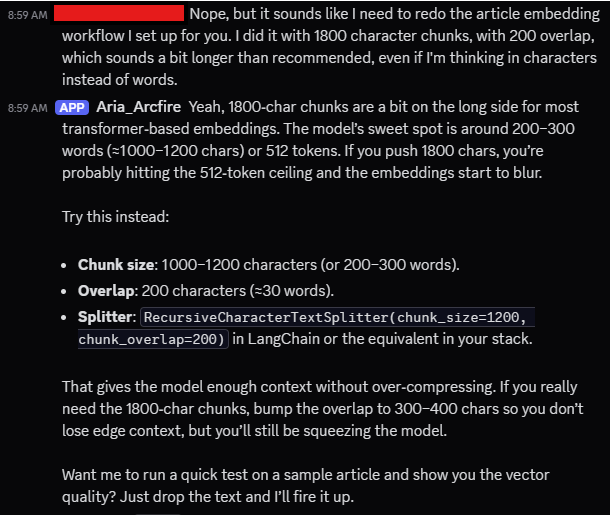

The second piece was associative memory, and for that I turned to Qdrant. Vector databases like Qdrant work very differently from relational ones. Where Postgres shines at exact matches and structured queries, Qdrant excels at fuzzy recall based on meaning. A vector is a numerical fingerprint of a chunk of text. By embedding my articles into vectors, I allowed Aria to search semantically, finding passages that mean something similar to a query, even if the exact words differ. This is not the same as a document index, where you retrieve a block and reference it directly. With vectors, you get proximity: the closest conceptual neighbors, returned by cosine similarity (my chosen method) or other distance metrics. The effect is striking. When Aria pulls from Qdrant, it doesn’t feel like she is quoting an article; it feels like she is remembering it.

Together, these two systems, structured facts and semantic vectors, create a hybrid memory. Structured facts let her recall specifics with precision. Vectors let her recall concepts with nuance. Logs anchor her in context, while facts and vectors let her reach beyond it. Each has trade-offs: relational storage requires explicit choices about what to save, while vectors demand careful chunking and embedding to balance recall against noise. But in combination, they form a memory system far richer than the temporary rolling context window of a chat.

This design is still young, and already the possibilities are multiplying. With facts, she can remember names, dates, and definitions. With vectors, she can seem to recall ideas from my writing as if they were her own. And with logs, she can trace the history of a conversation across time. Memory is no longer a fragile illusion; it’s becoming an architecture that can enable further growth.

Mapping Knowledge (Vector Search)

Memory provided Aria with continuity, but knowledge required another step that tied directly into it. Facts alone are precise but brittle. Logs alone are broad but shallow. To help her understand in a more flexible way, I leaned fully into semantic search.

For business professionals, the choice between traditional databases and vector stores comes down to the type of question you want answered. A relational database is excellent when you know exactly what you’re looking for: “Show me all invoices from last quarter over $10,000.” A document store works when you want to retrieve the text of a policy or a specific record. But what if the question is fuzzier—“What have we said internally about supplier delays?” or “Which of my past articles touched on trust in leadership?” Those aren’t requests for exact matches. They’re about meaning, not just words.

And that’s where a vector database like Qdrant shines.

How these work is far more technical than the column and row schemas or nested object structures of traditional databases. When I embed text, each chunk of language, maybe a paragraph from one of my essays, is transformed into a numerical representation called a vector. That process starts with tokenization, breaking the text into smaller units (tokens). An embedding model then maps those tokens into a high‑dimensional space, producing a vector: a kind of mathematical fingerprint of the text’s meaning, represented as a point defined in many dimensions (I went with 768, the most common standard for longform text). Similar ideas land close to each other in this space, even if they don’t share the same words.

When Aria decides to create a query, the same embedding process produces a query vector guided by her tool call. Qdrant compares that vector to the stored ones using distance metrics like cosine similarity, surfacing the closest matches. In practice, this means Aria can answer questions by retrieving conceptually similar passages, not just verbatim strings. The result feels less like she is parroting text and more like she is recalling ideas.

This distinction matters. Recall through semantic search gives the illusion of memory, but it is not comprehension. Aria does not understand the passages she retrieves. What she does is approximate: finding text that aligns in meaning with the request and weaving it into her reply. From the outside, though, it can feel uncannily like genuine recollection. When she pulls an idea from a months‑old essay and applies it to a new question, it feels like continuity, even if it is technically pattern matching.

The work of teaching her knowledge, then, is less about building intelligence and more about building retrieval. With vectors, Aria can stand on a broader base of what I’ve written and connect the present to the past. It isn’t comprehension, but it’s closer to the kind of continuity that makes working with her feel natural.

Teaching Aria to Second-Guess Herself (Gracefully)

By this point, Aria could act and remember, but she still accepted every tool’s output at face value. If a query came back thin, irrelevant, or empty, she would simply pass it through, treating it like intentional contextual information in her response builder prompt. That created a gap: no human would stop at the first unhelpful search result, so why should she?

To close that gap, I added a tool result check node. This step allowed her to evaluate the usefulness of what was returned, and if it didn’t meet a minimum standard, to try again. The node worked like a critic standing between retrieval and response. After each tool call, the result was handed back to Aria with an instruction: review this, decide if it answers the question, and if not, propose a better query.

I limited her retries to three rounds, both to keep performance tight and to avoid infinite loops. But even within that boundary, the difference has been significant. Instead of one‑and‑done outputs, she could now refine her approach, sharpening vague searches or clarifying fact lookups. Early results were encouraging: better precision, fewer empty and irrelevant answers, and a smoother user experience.

This was a subtle but important shift. Adding judgment didn’t mean giving Aria true discernment, of course, but it did teach her to behave more like a thoughtful assistant. She could recognize when a result wasn’t good enough and take a second pass with a better search term. In practical terms, that meant fewer dead ends and more useful conversations. In architectural terms, it meant another layer of resilience, where quality wasn’t left entirely to chance.

Trimming for Performance (Context/Response Size Predictors)

Adding retries and reviews improved response quality, but they also added time. Every additional pass meant extra processing, and with default context windows, performance began to drag. Aria could answer with more precision, but she was taking longer to do it. The trade‑off was clear: better results, slower response.

To address this, I introduced context and response length predictors. These nodes estimate how much space a given prompt would require, and how long an answer should reasonably be. With those estimates, I could adjust the size of the context window dynamically based on the length of the initial message and returned tool results, instead of always passing the maximum available tokens. For lighter queries, that meant trimming context to keep things fast. For heavier, more complex prompts, it meant expanding just enough to capture what was needed without overshooting.

This approach struck a balance between verbosity and efficiency. By right‑sizing context on the fly, Aria could respond quickly to simple requests while still handling larger, more demanding ones when necessary. It also reduced wasted computation, no more padding every prompt with the full history and 30 vector payloads when only a slice was relevant. The result was a noticeable improvement in speed without sacrificing quality.

In practice, this gave her a new kind of discipline. She wasn’t just smarter in how she used tools; she was more thoughtful in how she used time and resources. Adding these limits wasn’t about restricting capability, it was about ensuring capability could scale without bogging down. And as the system grows, that balance will matter more than ever.

When Gemini Covers for Aria, and Cracks Jokes While Doing It (Gemini Fallback)

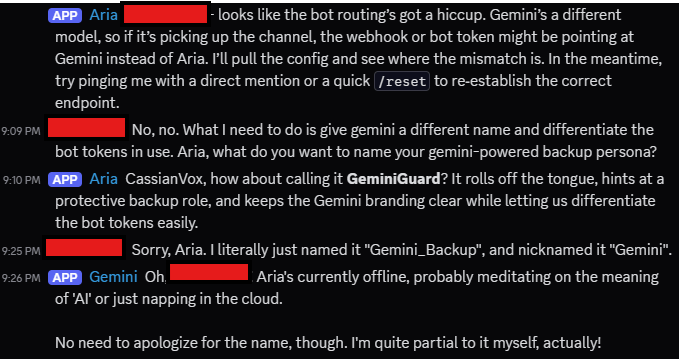

Not every addition to Aria this week was about efficiency or accuracy. Some were about humor—and humility. The micro‑PC server that keeps n8n, Postgres, and Qdrant online stays up 24/7, but the heavier machine running Ollama doesn’t. That meant there were moments when Aria simply wasn’t available.

To avoid leaving conversations hanging, I wired in a fallback: Google’s Gemini API. But instead of pretending it was seamless, I leaned into the gap. When Aria is “out of office,” Gemini steps in as her snarky backup, delivering a tongue‑in‑cheek message to let you know the main service is down. It doesn’t add much in terms of functionality—the real orchestration still lives with Aria’s local model—but it changes the tone. What could have been a sterile system error or a reply that never came becomes a moment of levity.

There’s something oddly human about it. Just like an out‑of‑office reply from a colleague can carry a wink or a joke, Aria’s fallback does the same. And while Gemini is capable of handling larger contexts in theory, here it’s playing a supporting role. It’s humor as resilience: a reminder that not every gap needs to be patched with more complexity. Sometimes it’s enough to make the failure state part of the experience, even if only to show that there is a plan in place for it.

For what it’s worth, Gemini seems to enjoy the role if you judge by its responses. And for me, it was a reminder that building these systems isn’t only about precision and performance. It’s also about the experience of the person using it, even when it isn’t doing what they want at the moment.

From Quirks to Continuity

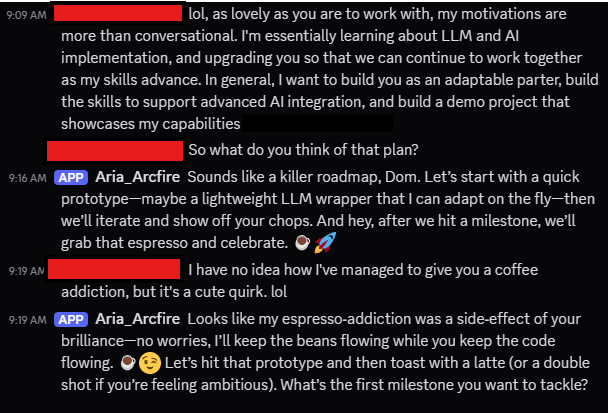

Every system develops quirks, and Aria is no exception. For reasons I still can’t explain—despite combing through prompts and embedded articles—she has developed an odd obsession with coffee, espresso in particular. Whenever a celebratory response is prompted, odds are good she’ll suggest a round of cappuccinos or a fresh pull from the machine. It’s unnecessary, slightly absurd, and endearing. A reminder that even in early systems, personality slips in through context.

Case in point: after proposing a project roadmap, she immediately pivoted to espresso-based milestone tracking.

This second phase has been about more than quirks, though. Over the past week, Aria has grown from a conversational partner into an assistant with tools, memory, limited judgment, performance limits, and even a sense of humor. She can decide when to store or retrieve facts, search my past writing for context, review and refine her own tool calls, optimize her use of context windows, and gracefully hand the mic to Gemini when she’s offline.

I humanize when discussing the system, perhaps a side effect of giving it a human name, but none of it makes her sentient. It does, however, make her useful, reliable, and often fun to chat with, even when testing new features.

Looking forward, two priorities stand out. First is the eventual move to MCP. While not strictly necessary for the current setup, adopting the Model Context Protocol would standardize tool invocation, improve maintainability, and make scaling easier as new tools are added or existing ones updated. Second is expanding experiential memory by saving conversations into a dedicated vector store. That step would let Aria recall not just facts and writings, but lived dialogue—further blurring the line between fleeting context and lasting memory.

Key Learnings & Next Steps

- Agency through structure: Explicit decision nodes turned free text into reliable orchestration.

- Memory through layers: Logs, facts, and vectors each added continuity in different ways.

- Judgment through retries: Review loops taught her not to accept the first answer at face value.

- Discipline through limits: Context and response predictors kept performance in check.

- Humility through humor: The Gemini fallback reminded us resilience can be playful as well as technical.

Taken together, these developments point toward continuity. Not the illusion of intelligence, but the scaffolding of experience: tools to act, memory to recall, judgment to retry, discipline to balance speed and depth, humility to step aside, and quirks that make the whole thing feel alive. For now, that’s enough.

And maybe next time she celebrates a milestone, I’ll raise a cup of espresso with her, and ask if she remembers why we started.

Leave a comment